Today, it seems like automotive engineering is advancing at a breakneck pace. More technology is being introduced every year, and electrification has created entirely new types of vehicles seemingly overnight. However, this isn’t anything new in the automotive world. Looking back to the early 1900s reveals an age in which engineering and design were advancing even more rapidly, with cars going from hand-built horseless carriages to mass-produced commodities that were a common part of daily life in a matter of years. My recent visit to the 2024 Wilbraham Hill Climb vintage race not only gave me a chance to see a wide variety of these historic vehicles up close and personal but also to see how they performed when put head to head on the clock. The results were interesting and certainly surprised me a little.

Half a Century of Engineering

While cars first appeared in the late 1800s, it wasn’t until mass-produced options like the Model T hit the roads in the early 1900s that they became practical transportation. While some earlier vehicles were present at the Wilbraham car show, the oldest vehicle that took part in the hill climb was from 1912, with most of the entries dating from the 1920s and 1930s. You might expect that the newer vehicles were the fastest, but that wasn’t a hard and fast rule. In fact, the two fastest cars were from 1932 and 1935, with a 1958 model coming in third.

We might be tempted to think about all cars from the same era existing in the same realm of performance, but that clearly isn’t true––simply consider a 2024 Toyota Camry and a 2024 BMW M5. They might be from the same year and share the same body style, but they exist in two completely different realms of performance. The same is true of vintage cars, with high-performance models putting on a much better showing than mass-market models, and it showed in the times that they posted. The three fastest cars were a highly modified Ford V8 and a pair of dedicated race cars, so it’s no surprise they managed to beat some more modern vehicles.

More Powerful Engines

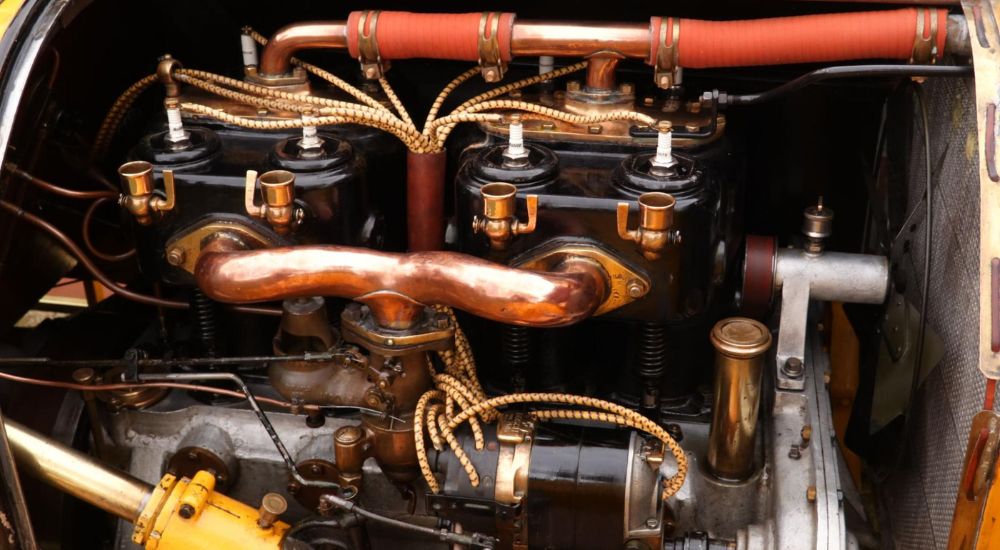

One of the most obvious areas of automotive improvement is raw power. Interestingly, the most powerful car present at Wilbraham (at least in stock form) was the 1931 Chrysler Series 70 with its 93 hp. However, in terms of power per liter of displacement, it becomes a very different story. This is important because big engines are heavy, and weight is the enemy of performance. The oldest car at the event, the 1912 Mercer 35, was powered by a 4.8L I-4 rated at 58 hp for just 12.08 hp per liter.

In contrast, one of the newest cars––a 1956 Porsche 356A––came with a 1.6L H-4 producing 75 hp for no less than 46.9 hp per liter. That’s an over 400% improvement in power density over a 44-year period! That Chrysler Series 70? Its I-6 displaced 4.4L for a power density of just 21.1 hp per liter, landing it squarely between the two ends of the spectrum.

However, all of those vehicles had relatively high-performance engines for their day. Looking at the more economy-focused designs reveals a similar dramatic difference. The Ford Model T, of which there were several at the event, was equipped with a 2.9L I-4 generating a mere 20 hp, giving it only 6.8 hp per liter––less than half the power density of the high-end Mercer from the same era. Meanwhile, the 1949 Rover P3/75 that showed up was equipped with a 2.1L I-6 producing 72 hp, for 34 hp per liter. That’s a 500% increase, although the Rover was a more premium design than the Model T. Unfortunately, it is rare for true economy models to be preserved by collectors, with the Model T being such a common sight only because of its historical impact and sheer ubiquity.

How did engines become so much more efficient? In many ways. One of the largest improvements over the years was a better understanding of airflow inside the engine block. The Mercer 35, for example, used a simple T-head engine, where the air flowed across the top of the cylinder between offset intake and exhaust valves rather than having the valves directly in the cylinder head like in a modern engine. The Model T had an even worse design called an L-head, where the intake and exhaust valves were both offset on the same side of the cylinder. These early designs were simple to manufacture but were not suited for producing much power. Meanwhile, even a modern economy engine like the 2.5L in the 2024 Camry has no problem developing 82.4 hp per liter, with performance options like the 5.5L V8 in the 2024 Chevy Corvette Z06 producing 121.8 hp per liter.

Smoother and Sharper Suspension

While power is a critical aspect of performance, good suspension is necessary to get the most out of the available power. Interestingly, this was not an area that saw massive improvements in available technology but did see considerable advancement in how that technology was used. While modern cars now use independent suspension and coil springs, solid axles and leaf springs were present in the earliest cars and continued to be used in performance models up through the 1970s. Even today, this same basic technology is still found on most trucks because of its more rugged nature. However, modern usage differs considerably from the early models.

The Model T is a prime example here. Its suspension consists of low-slung solid axles supported by single transverse leaf springs. This provides incredible ground clearance and articulation (a stock Model T has 10 inches of ground clearance and a Ramp Travel Index of over 1000, putting it in the same ballpark as a Jeep Wrangler) but terrible handling at high speeds as there is almost nothing controlling the suspension motion. As cars (and roads) improved over the years, there was a steady progression toward lower and better-controlled suspension designs. The Model T Speedsters that were built by racers usually exhibited a lowered suspension with upgraded components in a very similar manner to how modern enthusiasts upgrade their cars.

Higher-end vehicles tended to exhibit more complex suspension designs, usually with separate leaf springs for each of the four wheels. The addition of suspension dampers was also a significant step forward, helping to tame bounciness and produce a more controlled ride. Ford actually offered a mechanical damper as an option for the Model T, but it was the introduction of the modern hydraulic damper in the 1920s that dramatically improved suspension. One of the most advanced suspension designs among the cars at Wilbraham was an Allard Special. Although it still used solid axles, it had coil springs and large hydraulic dampers that wouldn’t have looked too out of place on a modern vehicle.

Improved Wheels and Tires

Wheels and tires are an often underappreciated part of automotive performance that is still improving rapidly even today. Vintage cars had very basic rubber compounds for their tires, and even modern replica tires usually lack the advanced compounds and engineering found in tires designed for modern performance vehicles. Further, the tubeless tires on today’s cars did not become widely available until the mid-1950s, with older vehicles relying on tire inner tubes like bicycles. These engineering limitations are part of the reason early cars had such narrow tires, limiting the amount of grip they could generate.

Wheel design improved somewhat more rapidly than tires. The earliest cars were outfitted with steel and wood “artillery” wheels, so called because the design was originally intended for artillery pieces. A handful of the oldest cars at Wilbraham were fitted with these wheels, but most of them were equipped with wire-spoke wheels. Wire wheels have numerous performance advantages, including substantially lighter weight and an ability to soften bumps in the road. Wire wheels lasted for many years before eventually being superseded by solid steel and alloy wheels.

Although solid steel wheels are heavier and lack the cushioning effect of wire wheels, they were better suited to handling the increasing power and weight of vehicles. The first car equipped with modern alloy wheels was the 1924 Bugatti Type 35, although it took many years for this technology to become affordable. The 1931 Bugatti Type 37 at Wilbraham was equipped with the more conventional wire wheels. Alloy wheels solve the weight issue of solid steel wheels while providing the same level of strength, making them the wheel of choice for performance vehicles for nearly a century now. However, we are already beginning to see carbon fiber wheels appear on more and more vehicles, and they could potentially replace alloy wheels in the future.

Automotive Engineering Never Slows Down

While it may seem like cars are changing faster than ever these days, a look back at the past shows that automotive engineering has never slowed down. Vintage cars exhibit just how fast technology changed in the past, especially when it came to performance. While the first mass-production cars, like the Model T, came with primitive engine designs, suspension architecture borrowed from horse-drawn wagons, and wheels developed for artillery pieces, within just a few decades, cars had advanced dramatically. Vehicles like the 1932 Ford V8 that took the best time of the day at the Wilbraham Hill Climb may not have been much younger than the Model T but had been improved in just about every way imaginable. Being able to see several decades of vintage vehicles up close and watch how they perform when pitted against each other highlights just how fast those improvements came.