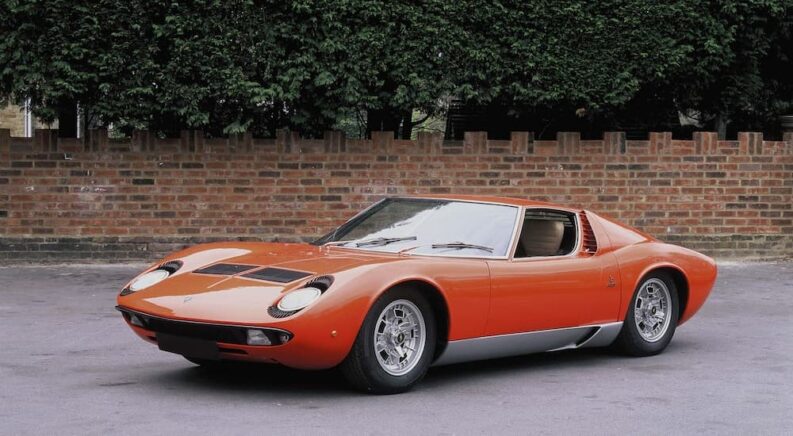

A remarkable collection of vehicles was offered at auction by RM Sotheby’s of London on November 5, 2022, named the Gran Turismo Collection for its members. It Included legendary Group B racers, the fabled Ferrari hypercar quintet, and a number of production car top speed record holders. The owner was obviously a speed junkie, unafraid of piloting some of the greatest achievements in the history of automotive engineering. Few models in the collection could possibly exemplify this more than chassis #4924 of the 1971 Lamborghini Miura SV by Bertone.

Most halo cars merely seek to attract car buyers to a brand. The Miura’s impact has been to serve as a halo car for the entire sports car industry. Its creation marked a divergence point in automotive history, leading directly to the development of many of the other members of the Gran Turismo collection. Today it remains widely regarded as one of the most beautiful and significant production cars ever made.

In the Beginning, There Was Nothing

At one point in time, no road car had ever boasted a rear-mid engine layout, and no race car had concerned itself with aesthetics or human comfort. There were road cars, and there were race cars, and that was fine.

Then Enzo Ferrari angered Ferruccio Lamborghini, a successful tractor manufacturer who owned two Ferraris. He kept burning out clutches, and paying 1,000 lire every time he had one replaced. Closer inspection revealed that these clutches were the exact same design that Lamborghini used on his tractors, and sold for 10 lire. When Lamborghini confronted Enzo Ferrari about this, Ferrari replied, “You are a tractor driver. You are a farmer. You shouldn’t complain driving my cars because they’re the best cars in the world.

“Oh, yes, I am a farmer!” Lamborghini angrily replied. “I’ll show you how to make a sports car and I will do a sports car by myself… to show you how a sports car has to be.”

I don’t care what people say, but there is nothing rational about getting ticked over an insult and responding by founding a new automobile manufacturer. It makes perfect sense that almost nothing coming out of Sant’Agata Bolognese in the past 60 years since has been the least bit rational at all!

Though it was preceded by the 350 GT, a successful if forgettable cruiser, the Miura’s release was Lamborghini’s Big Bang moment, instantly catapulting the brand to elite status. Every Lamborghini flagship since has been an instant icon. The Countach, Diablo, Murcielago, and Aventador are easily recalled, something I cannot personally say about Ferrari’s flagship supercars, great as each may be.

Featuring all the power and speed of a race car, the Miura also exudes a nothing-to-prove driving attitude that can’t be bothered with crushing hairpins as long as flying along the open road is still an option. As the first rear-mid engine car designed specifically for road use, and the fastest car in the world for the better part of 15 years, nothing better summarizes the Miura’s identity than to call it what it is: the world’s first supercar.

The Spirit of a Raging Bull

Masterminded by a group of daring 20-somethings, the story of the Miura is one of the greatest “Why not?” triumphs in automotive history. The tale reads like the plot of a heist movie.

It starts with Bizzarrini (yes, that Bizzarinni), who was largely responsible for the most expensive car in the world, Ferrari’s 250 GTO. He participated in a walkout at Ferrari known as the “palace revolt” and got himself fired. Not too long after, he was designing a brand new V12 engine for somebody else with a bone to pick in Maranello, the same engine which would power the seminal Lamborghini 350 GT, and shortly thereafter the Miura.

Then there’s Dallara and Stanzani, who drew inspiration from Ford’s soon-to-be world-beating GT to design a radically low monocoque chassis. There was just one catch: Lambo’s V12 was really long, and the wheelbase which would result from stuffing the engine behind the driver in a traditional longitudinal orientation was not going to be acceptable. Thus, the engine was mounted in transverse orientation, packaged in a single casting with the gearbox, like the original Mini, to make the most of the space they had.

Incredibly, it was at precisely this stage of development that the Miura debuted to the world, as a bare chassis at Turin in 1965. Yet Lamborghini left the show with ten sales orders in hand. The bodywork, drawn by a new designer by the name of Marcello Gandini of the legendary Bertone design firm, had to follow quickly. The now-timeless design, an alien beauty in the age of its debut, cut it so close to the 1966 Geneva Motor Show that when an interference with the engine was discovered, Ferruccio said to take the engine out, replace it with sandbags and bolt the cover shut for the show!

The ruse was a success, and the adjustments to rectify the issue were complete in time for Bob Wallace to market the car at the Monaco Grand Prix that same year, revving the attention-grabbing engine in front of the city’s legendary Place du Casino so people would make note of the breathtaking new sports car. It would enter production the following year, and underwent two mid-life refreshes that ultimately produced the rarest production Miura of them all: the SV.

Ahead of Its Time

The writing was essentially written by the time SV came along. As the first rear-mid engined road car in the industry, the Miura had made tremendous waves at Ferrari and Maserati, who both quickly adopted the format once its roadgoing viability had been so irreversibly proven. Weighing a mere 2,800 lbs while carrying one of the most powerful engines of the decade (making 345 hp), the Miura rocketed to 171 mph and in 1967 grabbed the “fastest production car” crown!

Though Ferrari’s 365 GTB/4 Daytona would nab the title the following year (the marque’s only official appearance on the list), the re-tuned Miura S made 370 hp and nipped at the heels of 180 mph in 1969. This was a speed which would not be surpassed until 1982’s Countach LP500 S finally relieved its predecessor of the crown, nine years after the Miura’s production ended.

The 13 consecutive years that the Miura spent at the top of the “fastest production car” list has never been matched. The McLaren F1 came close, holding the record for 12 years before the Bugatti Veyron decimated it. Thus, even the McLaren F1, regarded by many as the G.O.A.T., wasn’t quite as monumental as the Miura.

Let that sink in for a minute.

Chassis #4924

The Miura that was sold on November 5th bore chassis #4924. This was one of the 150 Miura SV models produced, which had even more power than the S, 380 hp, and a better suspension paired with fatter, nine-inch wide tires to handle it. Though these changes limited the SV’s top speed, it was undoubtedly a better car for it, creating a grand tourer the likes of which the world had never seen. Even today it impresses (for a vehicle of its era) once it’s up to speed on an open road, yet tragically, precious few of them often see that daylight.

Two unfortunate design flaws contribute to the hesitance of many drivers to run their Miuras. The first was the combined engine and gearbox, which could allow particulates from deteriorating gears to get inside the engine. Chassis #4924 is one of 54 Miura SVs to inherit this oversight, which was finally corrected for the last 96 examples of the car’s total production run. The second problem related to the Weber carburetors, which were positioned above hot engine and ignition components. Tragically, many examples of the world’s first supercar have gone up in flames, as excess fuel accumulates in the carburetors at idle and drips onto those hot parts of the car which were specifically designed to cause said fuel to explode, though preferably inside the cylinders rather than outside.

So it’s tough to blame the consignor for putting fewer than 200 miles on the car since they bought it in 2015, when they had it repainted from the factory Rosso Corsa to a strikingly vibrant Verde Miura. I was surprised to discover this. In my reviews of the GTC’s Ferrari hypercar quintet, I found that each had experienced a great deal of bonding time with their driver, so to see that the Miura was merely a concours showpiece is rather disheartening.

What is sadder is the full history of this Miura. Sold in US spec in 1971, it had accumulated a healthy 28,000 miles over 30 years by the time it moved to its fourth owner in Canada. There it was restored, with the odometer reset as if to erase its past, before being sold again in 2007 and transported to Kuwait. Eight years later, it joined the Gran Turismo Collection in the UK with astonishingly low mileage, replacing another SV whose fate is unknown.

Though it remains intact and almost entirely original, save for the odometer and authentic aftermarket paint color, I can’t help feeling sad that this car has seen such little road time. It seems to be a trend among Miura owners, as my attempts to compare other Miura sales from the last few years revealed mostly three-digit odometer readings, a couple references to an odometer reset, and many instances of no mileage being reported at all, making me suspect that mileage is something of a dirty secret in Miura-transacting circles. I can only hope that #4924’s new owner, who acquired it for a mere £2,058,125 GBP (about $2,560,760 USD), more than any of the Ferrari hypercars brought in, can find a way to balance the risk to their investment with the reward of enjoying one of the greatest open road tourers the world has ever known.

The Best of All Time

It’s now been almost 60 years since Lamborghini transformed the automotive world forever. The Miura struck like a raging bull, instantaneously elevating the brand to the status of a worldwide icon. A little over 30 years later, when I was growing up, I thought the entire car world basically revolved around Ferrari and Lamborghini. I didn’t think other “supercar” brands existed.

Isn’t there a certain incredible poetry to it? On the one hand, there’s Ferrari, the brand which invented “race on Sunday to sell on Monday,” whose sole focus was race cars and making the minimum adjustments needed to sell enough of them as road cars to keep the money flowing. On the other hand, there’s the brand who couldn’t give two flips about losing face to Ford and Ferrari at Le Mans, who only existed because the latter ticked them off, and in response they invented the supercar.

Though I only knew of the Diablo at the time (then Murcielago, then Countach), I would eventually know of the Miura. We should all know of and remember the Miura, especially since so many, like chassis #4924, rarely see the light of day, because it is specifically due to this car that all of our favorite supercars exist today.

The Miura was that right kind of something different and something new which had the power to shape generations of car enthusiasts. So few vehicles can claim the same level of paradigm-shifting influence that it isn’t far-fetched to call it the greatest car ever made.